Japanese architecture: is it really natural and sustainable?

Kengo Kuma and “natural architecture”

Japanese architect Kengo Kuma, who recently designed the V&A Dundee Museum in Scotland using locally sourced stone, is known for his extensive use of natural materials such as wood, paper and stone. In his book “自然な建築 meaning ‘natural architecture’”, (Iwanami Shoten, Publishers, 2008), he shared his amazement when he was met with an audience who were enthusiastic about “natural” Japanese architecture. Kuma noticed that these people were not only interested in simple and minimalist Japanese design but also held a high level of expectation that the Japanese approach was uniquely sustainable and in harmony with nature, and therefore had a new potential to become an alternative to Western and modern architecture – which was, obviously, a critical part of modern economy that was causing serious environmental degradation. So people often question Kuma to find out how sustainable his projects are: “I get a lot of questions such as “You use a lot of wood in your projects, but are you taking into account the risks of deforestation?” or “Using paper as walls seems very energy-inefficient, because it will increase fuel consumption in order to keep room temperatures moderate” or “I don’t agree with the use of plastic (which Kuma used in projects such as the “Water Branch House”), because it’s a petrochemical product that doesn’t biodegrade easily.””

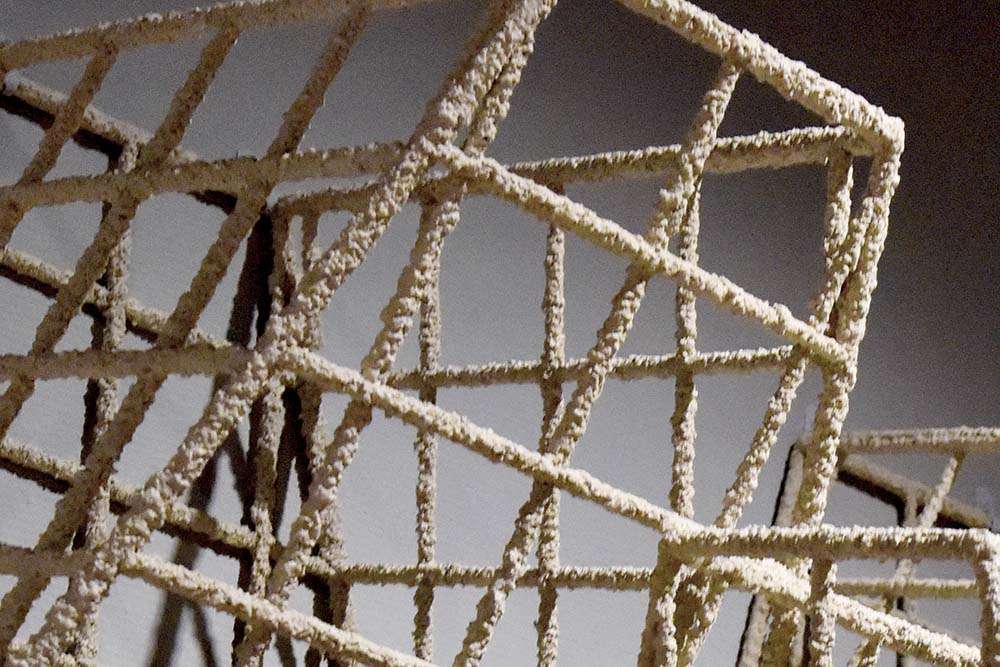

Kuma’s projects that used natural materials – from the exhibit ”Kengo Kuma: A LAB for Materials” held at the Tokyo Station Gallery, Tokyo, Japan in March 2018

Top left: Wood Top right: Paper (and washi, traditional Japanese paper)

Bottom left: Stone Bottom right: Earth

Curiously enough, instead of helping us get definitive answers on how sustainable Japanese architecture is, these questions wind up questioning where the notion of “sustainability” – a discipline of exploring an appropriate nature-human relationship – belongs, and where we belong. If you thought that Japanese architecture undeniably belonged to the world of science, then you belong to the Western/modern world.

It may sound odd, but as much as sustainability is part of environmental science that deals with subjects such as CO2 reduction, biodiversity or the technicality of recycling, sustainability is also about something else. At least it is for Kuma, who was born in Japan in 1954 when the country was still recovering from serious post-war resource shortages. Kuma admits that he felt a bit uncomfortable responding to these questions because “scientific sustainability” was not really the kind of nature-human relationship he has pursued through his architecture.

So he mixes and matches his answers: sometimes he gives answers using the same scientific platforms used in the questions: “Sure, it’s best to harvest/use/recycle wood in a way that results in the least impact. I would try to leverage the closest/most environmentally friendly supply sources.” But he also admits that he feels like nixing them on other occasions: “I do not 100% trust scientific methods that compute environmental impacts, such as energy efficiency of an architectural project, because you could get different results if you change any assumptions or variables used in the calculations.” Alternately, he tries to explain it by relying on a different life style: “The threshold for comfortable room temperature is different in different regions. Maybe Japanese people are okay with lower indoor temperature and rely much less on heating system to begin with.”

If it felt like he was dodging science-oriented questions, what he actually was doing was something much more fundamental: He was implicitly saying that science was not the only place where sustainability belongs, and that these questions did not best capture the essence of the kind of “sustainability” embraced by Japanese architecture. In traditional Japanese (or Asian) philosophy, the nature-human relationship is an aesthetic issue, long, long before it was a scientific one. If you’ve never quite comprehended the viability or practicality of Japanese-style naturalism, it may be because you missed this subtle but critical point. Scientific or aesthetic, that is the question.

Sustainability as an aesthetic issue

But how come sustainability is an aesthetic issue? In order to answer this question, we need to review what the nature-human relationship really is, and what “aesthetics” means.

Even though modern people almost forgot, nature is about the overwhelmingly large whole that embraces every single element/phenomenon that surrounds us. It’s far bigger and deeper than the mountains and lakes we visit during weekends. As it is mesmerizingly big and holds potential energy that could either foster or jeopardize peoples’ lives, nature is also a “chaos system,” which refuses to be predicted, tamed or controlled. All in all, it has remained beyond human ability to apprehend, therefore it is to be feared, admired and worshipped.

In such a world, humans had to mobilize every single ability in order to adopt to an often harsh environment. After tens or hundreds of thousands of years of effort, our ancestors accumulated enormous amounts of wisdom to progress and thrive. That is called resilience.

But as history progressed from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, science and technology emerged to completely and irreversibly change the game. They pushed the envelope to inspire the modern era, in which nature was no longer something to fear. With a wide range of new applications powered by fossil fuel, nature was now something to conquer and alter so that it served human needs. It was the Copernican Revolution that made the impossible possible; to completely change the way people lived, thought and behaved. As technology kept advancing, we felt that we have acquired a mighty sword which quickly overwhelmed our own wisdom and resilience.

Feeling victorious, we underestimated the unpredictability of the chaotic nature of the natural system. While we were busy enjoying the affluence technology brought to us, nature was quietly reacting to the changes we had made in ways we never expected, and before we knew it, serious damage had been done. That is where we are today. As we are increasingly made aware that technology is a double-edged sword that could backfire when misused, we are finally starting to correct our course. And since the problems were created from science and technology, our correction methods are also based on science and technology. That’s what we call sustainability.

However, Albert Einstein once said: “We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” If science and technology were the Goliath that created environmental problems, how can they be the problem solver? In that sense, the reservation Kuma has toward scientific sustainability seems legitimate. But is that the reason why sustainability should also be an aesthetic issue?

If you step back, humans already knew how to live sustainably by fearing, respecting and adapting to nature before modern technology swept the planet and degraded the environment. The answer was already inside us, in the breadth of wisdom and profound resilience our ancestors spent an enormous amount of time developing. But obviously, going back to the pre-modern life style was a non-starter. We want nothing but science and technology at the forefront in our fight against natural threats in order to thrive. The idea of going back to a pre-modern era terrifies us because it means losing the entire front line and being brought back to a defenseless, helpless situation. Even when working on subjects like sustainability in which science and technology were the very culprits that created the problem, there was no way we could sideline them.

But what if this assumption of “technology/modern or no technology/pre-modern” is wrong? Because it is. Even when there was little technology, the front line of our fight was never empty; it was always upheld by indomitable people. It was maintained by human wisdom and resilience. Remember what our ancestors accomplished by leveraging nothing but their own physical abilities, five senses and brain power only – without notepads, calculators or motor engines. Not only have they left miracles such as the pyramids or the Mayan calendar; they also cultivated/irrigated soil by reading local topology and climates; sailed (or “star navigated”) thousands of miles in a hand-crafted small boats; built high-rise towers from timber without saws, and traveled across large masses of indistinguishable tundra. They also compiled extensive mythological systems that reflected a mesmerizing/complicated universe even before they invented letters, and developed transcendental dances and rituals that were deeply rooted to the local environment.

Those works of resilience were the art of living – aesthetics. (Do not confuse them with primitive/poor technology) They were about finding beauty, happiness by making the most of what they had available, by unleashing every single ability they had and by challenging their limits. In regions where people traditionally lived very close to nature, including Japan, aesthetics was not just a design philosophy – it was a “code of conduct,” as you could infer from the way ancient people lived with mythologies. They were their personal/collective guidelines to behave gracefully toward nature (to which people had a one sided love-like passion) – to be adequately conscious about the surrounding environment; find things that would help them thrive; learn to leave nature alone when needed; and become creative in order to produce beautiful things that would make their lives happier and fuller.

The right question to ask in order to determine where sustainability belongs was not “technology or no technology;” it had to be “technology and/or aesthetics.” As long as sustainability is about striking the right balance between people and nature, aesthetics had to be the David that can counter Goliath, and the mental North Star that would guide science and technology by constantly reminding us how to behave beautifully toward nature. If science was about relying on external knowledge/power developed by a handful of smart people to deal with nature as “externalities”, aesthetics is about relying on each individual’s internal potential. If science was about trying to define chaotic nature, aesthetics is about embracing the chaos as it is. If science was about pursuing efficiency and stability, aesthetics is about exploring the beauty and happiness that defines your life.

Science and aesthetics have almost opposing roles and benefits. Neither of them can be avoided to pursue sustainability.

Is paper a sustainable construction material?

Kuma has been using “washi (traditional Japanese paper)” in his projects, which is very unconventional even in Japan. But it is an important material that defines his “natural” architecture. In his book, he remembers: “When I re-discovered that Japanese houses didn’t use flat glass until 1907, which is not that long ago, I was shocked. Just one hundred years ago, thin and subtle paper screen doors were almost the only partitions that separated the inside of Japanese houses from the outside environment. What a gentle and delicate way to leverage wisdom.” Traditional Japanese houses relied on pillars and beams, rather than walls as structure, and paper was primarily used in shoji and fusuma, removable screen doors placed between pillars. When it was nice outside, people would open them wide so that the entire room became a semi-terrace.

Paper used for shoji and fusuma had to be strong enough and come with great texture and translucency. In order to achieve this high quality, people traditionally grew specific plants (both for paper and coating), harvested and processed them properly, and applied highly specialized skills to finish them. Papermaking was a labor-intensive work of craftsmanship that required a lot of experience, and the end result was unbelievably high quality that and was used even as a material for bombs during WWII.

What Kuma sees in “washi” is aesthetic sustainability – the art of producing something extraordinary and resilient by making the most of what’s available in the natural environment and human wisdom/skills, and the art of resilient living right next to nature, and finding beauty and happiness through such a life style. He sees completely different opportunities in this kind of “natural architecture” which re-discovers what we’ve lost when we became too used to the concrete and steel-dominated architecture that separates people from the environment.

Unfortunately, those opportunities are difficult to pinpoint or define if you only rely on science. Cut and dried life cycle analysis cannot tell how people behind shoji screen doors can stay aware of the weather and adjust their activities accordingly in order to make most of it, as a paper screen lets the sunlight pass through it to produce semi-opaque, subtle but beautiful shades that softly tells you if the sun shines or how windy/rainy it is. A CO2 emissions calculator does not have line items to take into account the benefits of super localized, small and often mobile traditional Japanese heating devices such as kotatsu or hibachi, which can give warmth only when/where it’s needed. You could almost imagine how aesthetic-based sustainable architecture may fail to become LEED-certified.

Science is an act of defining. It’s inherently imperfect in the face of mesmerizingly chaotic nature, and it is exactly the question Japanese architecture brings up. The whole reason humans had to become resilient was because nature was so unpredictable and overwhelming. Even advanced technology cannot change it: it’s impossible to alter weather in our favor, for example. If that’s the case, should we focus on developing technologies that create the most efficient “isolation rooms” that shut down all kinds of “bad” things happening outside so that people could live easily and comfortably? Or, should we open up toward nature – good and bad – and try to learn how to make the most of “good” part and avoid “bad” part, in order to live resiliently?

It’s not easy to behave beautifully and sustainably. One of the reasons why aesthetic sustainability is unpopular is because it’s not easy. But then, life was never easy for anyone, and what humans do – either produce or consume – was never completely natural. We are always up against something, but the true beauty is in our fight to overcome it. Kuma concludes the book with acceptance of this reality: “…no matter how much I emphasize aesthetic goals, having to use petrochemical products, for example, doesn’t make me feel 100% proud. But then, are there 100% sustainable buildings, when you take into account the impacts associated with each and every material used, transportation, construction and/or demolition? The answer is no. I believe that it is important to acknowledge the fact that what humans make can never be completely natural or sustainable. We should accept this as a reality and start from there. Always remember to feel guilty about what we create, and keep asking a humble question: ‘Yes, our reality is imperfect. How can we do better tomorrow by making the best of what we have?’ That’s the only way we can achieve truly ‘natural’ architecture.”

Sustainable architecture according to Japanese architects

The notion of “aesthetic sustainability” is something natural and intuitive for many Japanese creators, including architects. While its manifestation in their works may often be elusive and sensorial, it becomes more obvious and tangible when they write. As many architects are inspiring writers, enjoy some of the excerpts from their books, in which they discuss truly beautiful nature-human relationships.

Natural architecture is “radical”

The 20th century was the era of concrete, a cost-effective, strong and highly editable material. Among other things, it helped decouple “surfaces” from the existence of any buildings so that people could apply fashionable make-up on them in order to increase their commercial value. While those projects made businesses rich, the race to develop technologies to show off cooler surfaces for better marketing had nothing to do with people’s rich, abundant life.

If we want to explore a truly rich life through architecture, we need to correct how it’s produced… Architecture has to be generated based on what the underlying environment offers, and on appropriate responses required by the location. The earth, or place/location I am talking about is not just the natural/topological background – it is where various elements/materials converge to support peoples’ productive activities, and vertically connect them with what the building represents…Truly natural architecture can only be possible when the act of “production” directly integrates with the place, people and the manifestation of the architecture; when it is deeply rooted in the underlying environment.

自然な建築 隈研吾 岩波出版 2008 (Kengo Kuma. Natural Architecture. Iwanami Shoten Publishers. 2008.)

Connecting inside and outside

Modern architecture is about creating an interior by setting solid boundaries that separate it from the outside environment. In this context, “sustainable architecture” often ends up meaning applying abundant insulation, shielding the inside from the outside in order to reduce energy consumption. But that’s not the “sustainability” I envision. Quite the contrary, I would like to connect inside (people) with the outside environment/nature as closely as possible – for me, it’s the only way to achieve true sustainability…For example, traditional Japanese houses used very few partitions/walls, as if the outside environment almost sneaks inside the house. Although it’s true that many modern people find living in such an un-insulated house uncomfortable/cold, I believe that the technology we have today is advanced enough to overcome the shortcomings of traditional design. That’s where/how we should leverage our technology – there should be potential to improve a lifestyle that is exposed to nature.

建築の大転換 伊東豊雄 ちくま文庫 2015 (Toyo et al. Great Transformation of Architecture. Chikuma Publishing. 2015.)

Architecture as a “future forest”

“I’ve always wanted to capture basic and universal elements that define our time in order to create new architecture…when I say “new,” it’s about the future that can never be realized…In that sense, the world we live in today is a stepping on board towards the future that we will never experience.

What basic elements define our time? It is information and environment. But I am not talking about the Internet or solar panels. “Information” is about new ways of simplifying things, and the “environment” is about external agents you can never control. I imagine architecture that simplifies what used be overtly complicated. I imagine a place partially hijacked by uncontrollable elements. How can I realize such architecture? How can I create profoundly a complicated/diverse place in a very simple manner?

One of the visions I have is “future forest.” A forest that is a simple whole that embraces mesmerizingly complex elements. A forest that is full of disturbances, but also packed with boundless opportunities, large and small. There is light. There are areas and places. This is my version of “new” architecture.

建築が生まれるとき 藤本壮介 王国社 2010

The Row House of Sumiyoshi (住吉の長屋), 1976

In 1976, early in his career, Tadao Ando designed the “Row House of Sumiyoshi” which was a low-budget renovation project of a Japanese traditional “nagaya” style small multiplex.

Partly because the budget was limited, Ando did not add any windows, or design any electricity/air conditioning. The house was hot in summer, cold in winter, and sometimes leaked when it rained. “It was world’s first zero-emission house,” Ando laughs cheekily.

So the puzzled owner would ask: “Ando-san, what should we do in winter when it gets cold?” Ando would reply, “Sure, why don’t you put on a sweater?” And the owner goes: “What if it’s still cold?” “Find more layers of clothes.” “What if it’s still cold?” “Sorry, there’s nothing more I can do for you. Go to the gym, add layers of muscles so that you can live with it!”

Whereas it may sound like a poorly prepared project, Ando actually put a lot of philosophical experiment into this small project to connect people directly to raw nature. Found out more about his wildly powerful perspective.

Reference

If you are interested, check out the Washi master Yasuo Kobayashi, who has been working with Kuma to provide resilient paper products.