Tadao Ando: Endeavors – The Row House of Sumiyoshi

Japanese architecture in the 1970s

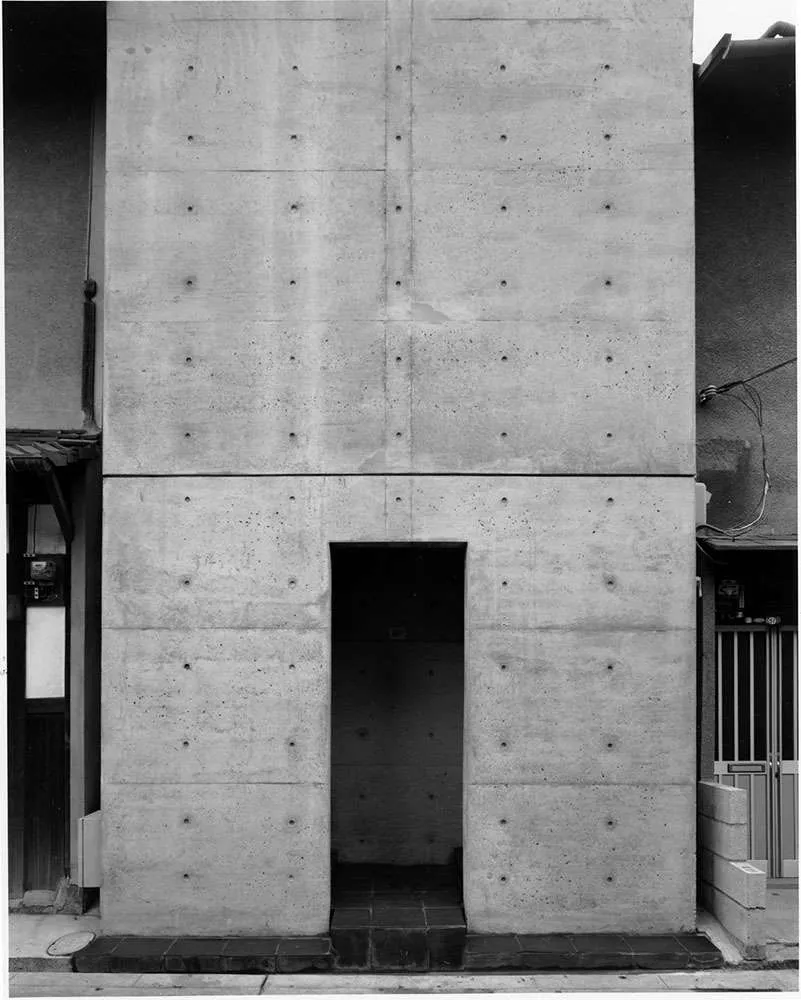

The “Row House of Sumiyoshi” is one of Tadao Ando’s earliest and most famous works. It was sensational and controversial in many ways. When it was completed, some people criticized it while others absolutely loved it. It received the Architectural Institute of Japan Prizes in 1979, which made him a nationally recognized architect.

Ando designed the “Row House of Sumiyoshi” in 1976, and Toyo Ito designed “White U” in the same year. Toyo Ito recollects the era: “From the end of the 60’s to early 70’s, young, budding architects were excited about the Metabolism movement. But the Osaka International Expo in 1970, which was supposed to be the calumniation of the Metabolism architecture, was disappointing. We sort of lost our sense of purpose. I wasn’t sure where to go. I think our generation stopped pretending that architecture could change the world. It felt more appropriate for us to explore our inner world through our design.”

Indeed, the Row House of Sumiyoshi was a concrete box that had no openings that connected it with the community. However, it had a small patio inside the house that opened it toward the surrounding environment. Ito’s assessment was correct that young Japanese architects in the 70’s experimented highly introvert design style.

The Row House in Sumiyoshi, 1976, Osaka, Osaka

Photo by Shinkenchiku-sha

The Row House of Sumiyoshi Project

住吉の長屋, or the “Row House of Sumiyoshi,” was a renovation project of the middle unit of a Japanese traditional “nagaya” style multiplex that connected three small traditional wooden houses. The project was , therefore, sandwiched by two similarly small nagaya houses. The owner asked Ando to demolish the old structure and build and furnish a new home with the budget of only about $100,000. Because of the setting, the project had limited flexibilities, but the owner requested Ando to somehow stay connected with the outside environment.

But how would you do that? Ando himself grew up in nagaya. So he transfused his own nagaya experiences into the new house – in an unexpected and bold way.

The Nagaya that shaped Ando’s architecture

The nagaya has a long history in Japan. Although the format has existed since the Middle Ages, it became popular in the Edo era (1601-1868) as the population grew in Japan and urban/commercial areas expanded. It was a horizontally long structure divided into many small units in order to accommodate as many families as possible in a limited space. Each unit was a small, narrow rectanglar space with only a couple of rooms. The entrance was on the short side.

The nagaya was the opposite of modern homes in every way. It was small. It shared structure and the surrounding environment with the neighbors providing little privacy. It was wooden, frail and susceptible to the threats posed by the weather. The evolution of modern homes has almost been equal to overcoming the discomfort associated with the traditional living environment such as the nagaya.

Ando’s own experience growing up in nagaya was not easy either. In winter, chill winds would leak into the house through broken windows, freezing the 10 year-old Ando under his thin blanket. The storm would rattle the entire structure. The rooms in which he did homework became dark as the sun set. Bugs and pests would sneak in. The neighborhood was full of kids and the fights erupted all the time. But for Ando, the “discomfort” he experienced living in nagaya was never something he wanted to eliminate as an architect so that the modern world could pretend that it did not exist. Quite the opposite, it was what shaped his strength and resilience, and his philosophy towards architecture and life.

Living in the nagaya, he learned to appreciate the overwhelming power of raw nature, which was both a threat and a blessing. Summer could be painfully hot and sticky, and winter could be grim, frosty or icy. But the same harsh nature delivered beautiful light, water, abundant beauty and precious resources. From Ando’s perspective, nature has always been dual. It had bright side and dark side. It was embracing and menacing. It was kind but brutal.

Such duality made humans resilient. Faced with the overwhelming power of nature, people thought, tried, failed, tried again and endured. It was this honest collision of nature and humans, and the resilience humans exhibited that formed Ando’ fundamental philosophy that architecture needed to be “experienced.” And when Ando says “experience,” it means experience fully, not just the comfortable side of nature.

The Plan of the “Row House of Sumiyoshi”

Model of Row House in Sumiyoshi (Osaka) ©安藤忠雄展2017

His plan was to insert an almost completely closed, no-frills concrete box, which would be sandwiched between the wooden nagaya units. As you can see, there are no windows on the blank walls. There was no electricity or air conditioning either. It almost looks as if it was completely isolated from the outside environment. But of course, that was not how nagaya was traditionally designed, nor how Ando viewed the relationship of the environment and humans.

So Ando inserted a traditional nagaya device in the middle of the house: a small patio. Since the traditional nagaya (and also the machiya) was the collection of small houses standing close to each other, they typically had small patios called tsubo-niwa or tori-niwa (pass-through patio) in the middle of the house in order to secure sunlight and ventilation.

Ando embedded a tori-niwa patio in the middle of the house, which was literally a pass-through. It cut the entire house into two completely separated areas, and the residents had to walk through the patio in order to reach the other side of the house. For example, the bedroom was at the front and the bathroom was at the rear end. When it rained, people in the bedroom had to use an umbrella to cross the patio, just to go to the bathroom. When it was cold, it was hard on their feet.

Because there was no heating, the owner would ask: “Ando-san, what should we do in winter when it gets cold?” Ando would reply, “Sure, why don’t you put on a sweater?” And the owner goes: “What if it’s still cold?” “Find one more layer of clothes.” “What if it’s still cold?” “Sorry, there’s nothing more I can do for you. Leverage your physical power and live with it!”

“Sustainable Living” according to Ando

It that was not enough, Ando added a small opening in the ceiling of the entrance through which the rain would come in. And because there was no electrical lighting, the residents had to leverage the sunlight coming through the patio. (But this must be where Ando’s mastery to marry the surface of bare concrete and the rays of light started.)

This is definitely not what we think of as “sustainable living” or “living in harmony with nature” in the modern context, but Ando jokingly declares that it was the first 100% “net zero house,” because it used no electricity. For Ando, nature always had to be whole, and living was almost equal to survival. That’s how he grew up, and that’s how he perceived the relationship between nature and humans, and between society and himself.

Togo Murano, a renowned architect who, at the time the house was built, sat on the committee of the Yoshida Isoya Award, saw the “Row House of Sumiyoshi” and said: “The award should be given to the brave owner who is living and surviving in this environment.” The house eventually won the Architectural Institute of Japan prize in 1979, which made Ando a national figure. People were stunned by his fearless approach to challenge the convention of the traditional house, the use of concrete, the way he managed a low budget project, and especially, the way he questioned what it meant to “live,” and what a house was supposed to deliver to the residents.

Ando’s approach is eye-opening for us who live in the modern environment. When we think about “living in harmony with nature,” we only think about the nice, beautiful, comfortable side of nature. But Ando reminds us that we are missing half of the real face of nature.

He does not want to us to forget. Even when people criticize his works because they are cold to live in or because they leak, he is not willing to compromise. He wants to remind us of how strong mother nature is. He wants each of us to think what we can do to deal with it. It is what Ando means to live with nature. He is a strong believer of human resilience, which could easily be forgotten if we pamper ourselves in a comfortable, convenient and easy living environment.