Ambiguous architecture according to Japanese architects

Ambiguity (aimai) in Japanese culture

Can ambiguity play a role in architecture? At first glance, the answer seems no, as buildings must have structural strengths to ensure sturdiness, durability, and safety. You may compromise them if you make any building parts ambiguous.

However, 曖昧 (aimai – ambiguous, vague, or ambivalent) has been a familiar concept in Japanese architecture. Aimai has been one of the unique aesthetic characteristics of traditional Japanese culture, and Japanese embrace aimai in pretty much every aspect of their lives (Do you know a Japanese or two who confused you by giving vague answers that sounded both yes and no?)

If you are into Japanese culture, you may have heard 余白 (yohaku) or 間 (ma). Yohaku is spatial, ma is temporal voids (ambiguity) left in between tangible things.

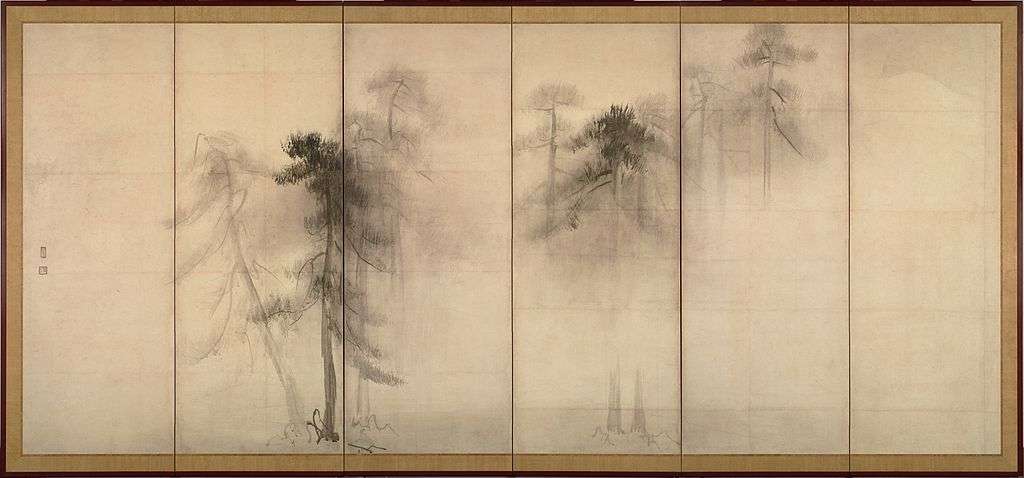

Hasegawa Tohaku (1539-1610). Pine trees.

One of the most recognized pieces of traditional Japanese painting.

Hasegawa left abundant yohaku (spatial voids) in it.

When ambiguity such as yoyaku or ma is left in between two things (A and B), it has potential to become A, B, the mixture of A and B, or none of them, depending on time of the day, weather, users, audience, type of event, so and so forth. This cannot happen if you defined two things without leaving ambiguities in between. You can only have A or B, and you are forever stuck with them. Ambiguity in aesthetics is about boundless potential, as it can become whatever it wants to be, or you want to see in it.

Ambiguity (aimai) in traditional Japanese architecture

Traditional Japanese architecture has had something similar to yohaku or ma, partly helped by its relatively mild climate and safe community environment.

Ambiguity in architecture: 障子 (shoji)

Shoji is detachable screen door or partition. Thanks to a rather mild climate, Japanese could choose feeble and thin materials – paper and wood – to close rooms. Paper is translucent; it can let sunlight come through, or vaguely show the shadows of outside objects. The face of shoji changes depending on the time of the day, or weather. You can take it out to open the room toward outside. Shoji connects the interior and exterior ever so ambiguously and subtly.

Traditional Japanese minka (ordinary people’s house) with thatched roofs.

Left is seen from outside, right from inside.

Notice shoji reflects not only sublet light but also greens outside.

Ambiguity in architecture: 坪庭 (tsuboniwa)

坪庭 (tsuboniwa) is a tiny garden or patio usually placed in between building units, especially 長屋 (nagaya) or 町家 (machiya), which were very narrow residential multiplexes ordinary Japanese people lived hundreds of years ago. Tsuboniwa is described as “quasi-indoor gardens,” as it is designed to be directly accessible from adjacent rooms. Although it may not make sense to have a small garden in an already small house, tsuboniwa was a multi-functional device that made small living space enjoyable by providing passage ventilation, increased light (especially important in pre-electricity era), sense of openness, and an aesthetic accent. Japanese made sure to leave some ambiguous place even in small living spaces.

Japanese tsuboniwa.

Left: it must be winter. The trees are covered to protect them from low temperature

However, ambiguous areas are disappearing from Japanese communities because modern building codes and standards require solid structures, which don’t allow much ambiguity. Also, people today are concerned about privacy, security, safety and keeping room temperatures comfortable. (I grew up in a house with shoji. It can get pretty cold!)

Things aren’t looking good for ambiguity. So Japanese architects are trying to be creative to re-discover the beauty of ambiguous architecture using new approaches.

Sou Fujimoto and ambiguous architecture

Sou Fujimoto leverages ambiguity in his works. He intentionally leaves undefined areas or functions so that they can increase options and potential how pieces of architecture can be used or enjoyed.

He grew up in rural Hokkaido (Northern part of Japan) surrounded by woods, and had always been fascinated by the complexity of nature. He liked how a countless number of small elements created a large, “chaotic” whole such as a forest. Each element that constitutes a forest would keep moving or changing, which would constantly change the faces of different segments. But no matter how things change inside, the whole will maintain its wholeness. For Fujimoto, the combination and interaction of ever-changing small elements inside a large chaos was the source of potential that could make the whole full of wonder. He saw that Tokyo functions in the same way: it’s made of a countless small units to make a huge metropolis. He saw that it was the interactions and dynamics of every-changing, undefinable small elements that made Tokyo an exciting city.

For Fujimoto, ambiguity is a source of potential, as undefined elements can become A, B, A and B or none of the above.

Kengo Kuma and architecture that yields

Kengo Kuma is also very aware of the potential Japanese aesthetics can play in architecture. Just like how his ancestors did hundreds of years ago with wabi sabi concept, Kuma unearths seemingly negative concepts for architecture including small, weak, yielding or shabby. But you wouldn’t want weak or losing buildings. What does Kuma really mean?

Kuma is not a big fan of modern architecture that is all about shielding peoples’ living spaces from the outside environment. He does not agree that cutting our ties with the natural environment for the sake of safety or efficiency increase our happiness. As he keeps pursuing ways for people to stay connected with the environment, he taps traditional Japanese wisdom, which is basically the realization or acceptance that Mother nature is a lot stronger than us. Instead of trying to conquer or defy the threats posed by nature, Japanese tries to conform to it, which was about accepting its smallness and weaknesses. By leveraging such wisdom, Kuma attempts to leave some ambiguous areas between the natural environment and peoples’ living spaces. How how does he do it?

Toyo Ito and the future of architecture

You may have realized by now that Japanese architects often re-discover ambiguity in traditional Japanese sense when faced with Western-style solid, logical principal that tries to precisely define every element. While it has its strengths, which is obvious, it has its own shortcomings. As Western-style architecture is on the way to cover every corner of the world with massive amount of steel and concrete, causing environmental destruction and making them all alike, ambiguity could play a role to help us re-think what it takes to create a happy community, not an efficient, economic one.

Toyo Ito looks at Asian architecture, as he sees new perspectives there for the future. Read his interview.