Is Kengo Kuma’s architecture really sustainable?

Japanese architect Kengo Kuma’s style is often called “natural architecture,” because he almost always uses natural materials such as wood, stone and paper. But is his architecture really sustainable? When Kuma wrote “自然な建築 (Natural Architecture, Iwanami Publishing, 2008)”, he dedicated the last chapter to the exact question: “Is natural architecture sustainable?” Find out what he had to say.

How is Japanese architecture perceived?

The chapter is based on Kuma’s experience giving lectures in many places around the world. First, he wrote that his audience perceived Japanese (or Kuma’s) architecture as an alternative to Western or modern architecture. Traditional Japanese architecture prioritized staying in harmony with nature, and refined Zen or wabi sabi-influenced minimalist design. According to Kuma, people were excited about the potential of Japanese philosophy and design aesthetics. They hoped that they could be leveraged to tackle issues like excessive urbanization or sustainability.

That’s why the audience are eager to ask Kuma sustainability-related questions: “You use a lot of wood in your projects, but are you concerned about deforestation?” “Using paper as walls seems energy-inefficient. Wouldn’t it end up using more energy for heating?” or “I don’t agree with the use of plastic in your projects.”

Kuma’s answers to sustainability questions

So how does he answer? Interestingly, his answers are rather ambivalent.

For relatively straightforward issues such as how to use wood sustainably, his answers are also straightforward. For example, he would say: “It’s best to harvest and recycle wood to minimize the impact. I leverage local resources as much as I can. It’s especially important in Japan, as Japanese timber is struggling to compete against cheap imports. It also reduces CO2 emissions associated transportation.”

Wood, especially locally sourced wood, is Kuma’s signature material. See “The Bamboo Wall,” “Bato Hiroshige Museum of Art,” “Yusuhara Wooden Bridge Museum,” and also the “Wood section” from his exhibition “Lab for Materials.”

Kuma’s answers to thorny sustainability questions

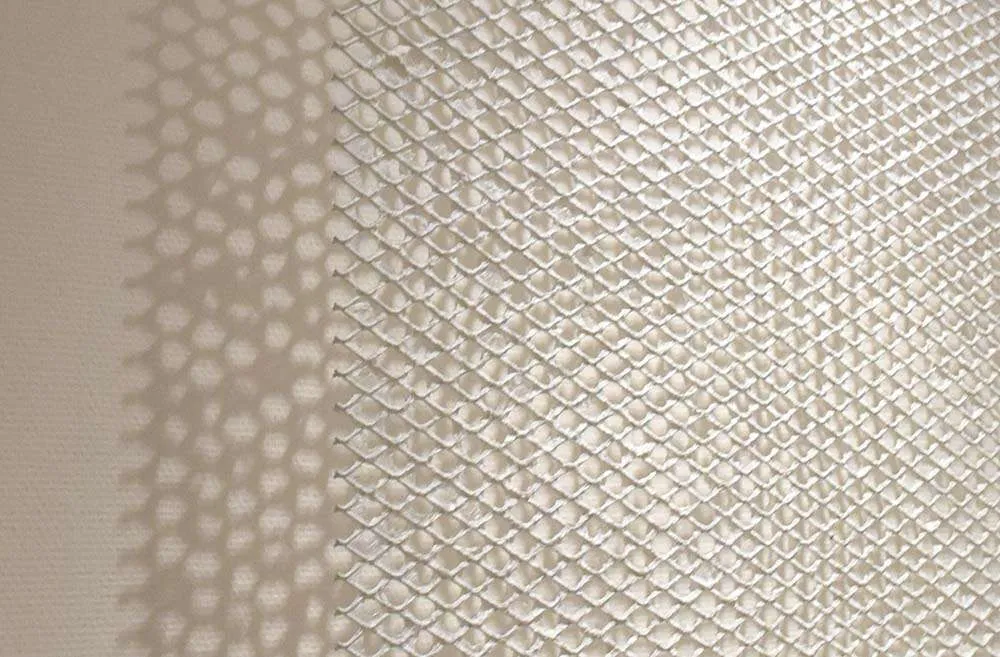

But other questions are more complicated. Take the use of paper as a construction material. Paper may be a natural material, but what’s the point of using it as part of walls? If you are from a country where a house comes with sturdy walls, it may especially be unfathomable to use frail paper as part of partitions/walls. It’s obvious that paper provides little security/insulation.

Paper may look pretty, but it’s not functional at all, you might think. Kuma knows that, too. Then why does he still want to use paper? It’s a long story, so please read “Paper” section of his exhibition “Lab for Materials.” His passion for paper is almost equal to what he believes “natural architecture is or should be.

One important clue: Japanese have been using paper as partitions for hundreds of years – remember shoji and fusuma – and it’s been part of how they interacted with the surrounding environment. If your living environment helps shape your behaviors, paper forced Japanese to change the way they lived, because of its poor insulation capacity. They had to learn to adjust to the ambient temperature flexibly by creating a variety of super localized heating/cooling devices such as kotatsu tables, change how you are dressed, and making the most of the sunlight. In traditional Japanese life sytle, it wasn’t really the HVAC system that’s adjusted to the environment; it was people who were the solutions to live sustainably. Kuma is a huge believer of what people can do to live naturally and sustainably, which is a factor that cannot be quantified by any sustainability metrics we have right now.

Yet another thorny question is the use of “unsustainable” materials such as plastic. For example, Kuma designed a “tea house” called “Tee Haus” for a museum in Germany using polyester, because he saw new potential in the material’s softness and flexibility. He also showcased the “Water Branch” at the MOMA exhibit, which consisted of plastic modules anyone could connect in order to create a building structure. It’s been Kuma’s dream to offer a design literally open to anyone – no architectural expertise or strength to lift heavy materials required. He passionately believes that architecture that is open to anyone can create a new potential for the future or modern architecture, which became too large and complicated. Kuma reflects that he couldn’t find any other materials that were better than plastic in terms of lightness, flexibility, accessibility, availability, and affordability. Of course he is not happy with the fact that plastic is petrochemical. But at least he believed that it shouldn’t stop him from experimenting new potential to open architecture to people.

Left: “Tee Haus”

Right: “Water Branch”

Kuma admits that his projects won’t always score A++ if they are judged using science-driven sustainability metrics. He also admits that there are much more he or architects can do to make buildings as sustainable as possible. But he also recognizes that it’s a tall task given the fundamental nature of architecture: no material, no project is completely free of environmental impacts. What we do inevitably result in some impacts one way or the other. He believes that the most important thing is that everyone involved in a project to remember that – we are creating environmental problems. We need to be humble, Kuma says, and accept it. Then humbly keep trying to make things better every time, by doing what’s realistically possible and doable. Don’t stop, keep trying until we get there.