What is sukuya-zukuri, traditional Japanese architectural style?

Sukiya-zukuri is one of the traditional Japanese architecture styles that you probably picture when you hear “traditional Japanese architecture.” It originated from 茶室 (chashitsu or tea room/hut) used for wabi-style tea ceremony, which was cemented by Sen no Rikyu, the legendary Tea Master in the 16th century. As the word “wabi” suggests, wabi-style tea ceremony was the culmination of “wabi-sabi” culture, and chashitsu architecture was the manifestation of wabi-sabi philosophy.

Zen-influenced Tea Masters, including Sen no Rikyu, denied conventional protocols, rules or beliefs and designed chashitsu that radically pursued simple, natural or raw elements while avoiding decors or frills as much as you possibly could. It was the opposite of shoin-zukuri, the then-conventional architectural style that respected formality. So sukiya-zukuri is about designing buildings free from conventions or protocols.

You can find interesting design details or bold adoption of unlikely elements in sukiya-zukuri.

Left: The Izumo House. Right: The Shimai Manor.

Photo-Tetsuya Ito/by courtesy of DISCOVERLINK Setouchi

Setouchi Minato no Yado

Japanese residential architecture has changed significantly over a couple of centuries, reflecting the drastic social transformation in Japan (modernization and Westernization) and the fact that older houses predominately used wood which required significant maintenance. Traditional pre-WWII houses were demolished everywhere over the past decades, only to be replaced by Western-style commercial units. Even though it almost seemed as if the old buildings were on the verge of extinction, today that trend is slowly changing. Alarmed by the rapid disappearance of traditional buildings with priceless historical values, local people in many regions are taking action to preserve/renovate them so that they can become again an integral part of the community.

In scenic/historic Onomichi City, Hiroshima, you can stay in such traditional buildings. Local business, Discoverlink Setouchi renovated and converted two old buildings, originally built during 18th ~ early 20th century into classy and comfortable accommodations. Named the Setouchi Minato no Yado, the two buildings sit on a scenic hill in Onomichi, overlooking downtown and the stunningly beautiful Seto Inland Sea. The traditional (sukiya)-style house is called the Izumo House, which was originally built in the Edo era (1603 ~ 1868) and then expanded in the Meiji era (1868 ~ 1912). The second house is called the Shimai Manor which was built in 1931 in a Western style.

These unique accommodations are not a hotel. Rather, you rent the entire building (or half of it) and it’s all yours. Since both units attempt to preserve as many old details and materials as possible, you can feel the lives of the people who used to use them hundreds of years ago. It is quite an experience.

出雲屋敷 (the Izumo House)

The Izumo House was originally built as a single-story trading branch sometime around the 18th century by the (feudal) province Matsue-han, about 180 km away from Onomichi. It was the first non-religious building situated on the hill, which traditionally only allowed shrines and temples because people considered the area sacred. It tells us how important Onomichi was as a trading hub for the regional economy, and how the economy was changing the social hierarchy in 18th century – merchants were becoming as powerful as military/religious elites. After the Meiji Restoration (a revolutionary regime change from feudal to a modern system), the building was bought by one of the prominent local merchants who added the second story to convert it to a guest house. By that time (in which the social hierarchy that had the “samurai” at its top was abolished), rich merchants had enormous social influence.

Photo-Tetsuya Ito/by courtesy of DISCOVERLINK Setouchi

The Izumo House is located in the middle of a beautiful hill in Onomichi.

In Onomichi, trading merchants who accumulated wealth and power led the community and social scene. While they secured their offices on the coast close to the ports, they loved to build villas/retreats on the scenic hills in which they entertained their guests and hosted elegant parties. The style was influenced by the 茶道 (sado, or tea ceremony), and the houses typically applied the 数寄屋造り (sukiya-zukuri), accommodating 茶室 (chashitsu, or tea room). This style that Onomichi merchants developed was called 茶園 (sa-en) culture. “茶” means tea (or tea ceremony), and “園” means garden, so you could almost guess what it was all about.

The renovation of the Izumo House was supervised by a prominent Japanese architect and the “sukiya-zukuri” expert Masao Nakamura. 数寄屋 (sukiya) is a traditional architectural style that emerged sometime during the 16th century, and is still used to design traditional houses, restaurants and hotels today. According to Nakamura, sukiya-zukuri is about “庭屋一如 (teioku ichinyo)”, meaning that the garden and the building need to be one and dissolve into each other. Influenced heavily by the sado (tea ceremony), the sukiya-zukuri pursues natural beauty instead of decorative, ostentatious details. It also avoids rigid traditional architectural protocols because it prioritizes aesthetics over to prestige or order.

At the Izumo House, you can feel the essence of the sa-en culture and the sukiya style that flourished during the 19th ~ early 20th century here in Onomichi.

月 (tsuki): the ground floor

The ground floor is called tsuki (moon) because it has a 月見台 (tsuki mi dai, or moon-viewing deck).” It also has traditional a chashitsu (tea room), a zashiki (guest room) and a dining room.

Photo-Tetsuya Ito/by courtesy of DISCOVERLINK Setouchi

The approach and entrance of the Izumo House.

座敷 (zashiki, the guest room)

In general, the zashiki = guest room is the classiest room in a Japanese traditional house. It has the 床の間 (tokonoma, or the raised area used to display calligraphy, ink paintings and/or flower arrangement), which defines the room layout and dimensional priorities. The tokonoma pillar used for the front/center is called “床柱 (toko-bashira)” which plays an important aesthetic role. A very authentic tokonoma uses the square timber (with smooth angles) of hinoki (Japanese cypress – the highest quality timber in Japanese architecture), but more casual ones or chashitsu use round timber with different finishing touches. But in any case, the timbers are never treated or painted. You enjoy the natural texture/slants of different wood species.

月見台 (tsukimi dai, the moon viewing deck)

Moon viewing (and writing tanka-like poems about the view) used to be “classy” entertainment among the social elites for centuries, until electric lights started to purge darkness from the night sky and make moonlight look less gorgeous. Situated on the top of the hill overlooking the glassy Seto Inland Sea, the moon-viewing deck of the Izumo House must have delivered a stunning view. (It is now obscured by shrubs and trees to provide an intimate, private space.)

Photo-Tetsuya Ito/by courtesy of DISCOVERLINK Setouchi

Don’t miss the dusk hours at the Izumo House. Turn the room lights off and enjoy the subtle show as the light gradually submit to darkness.

茶室 (chashitsu, the tea room)

The chashitsu is a small room exclusively designed for the tea ceremony gatherings, but it is much more than a “hobby room;” it represents the essence of the sukiya-zukuri. It is so because the sado (tea ceremony) emerged as a quasi- “code of conduct” when what we perceive as “traditional Japanese culture” today cemented its foundation during 14th ~ 16th century. The sado, heavily influenced by Zen Buddhism, urges the visitor to look every aspect of their life through the lens of aesthetics and art of nature, not through social rules or standards dictated by people in power. The chashitsu served as an aesthetic/philosophical lab to let people practice the sado-ism.

That is the reason why the chashitsu holds a symbolic place in traditional Japanese culture. Having the chashitsu as an integral part, the sukiya-zukuri declared that it would pursue natural beauty by eliminating excess frills and denying rigid architectural protocols. In addition to this radical smallness, the chashitsu often uses bucolic materials, skips certain construction processes or replaces authentic design with rustic details in order to embrace nature as it is. You can see many elements that constitute “sukiya” in the chashitsu.

NOTE: The descriptions are about the tea room in general and not necessarily specifically about the tea room at the Izumo House.

The entrance to a chashitsu is small and often requires you to bend your back. That action prepares your mind for an inner journey instigated by the tea ceremony. The small square tatami sheet you see in the right hand picture is where the “ro” (a small hearth to boil water to make tea) is situated.

The hospitality begins with the hanging scroll displayed in the tokonoma which could be an ink painting or calligraphy. The host chooses the most appropriate piece of art, taking into consideration the season, the weather, the guests and their relationship to the host. Flowers often accompany the scroll, adding seasonal accents.

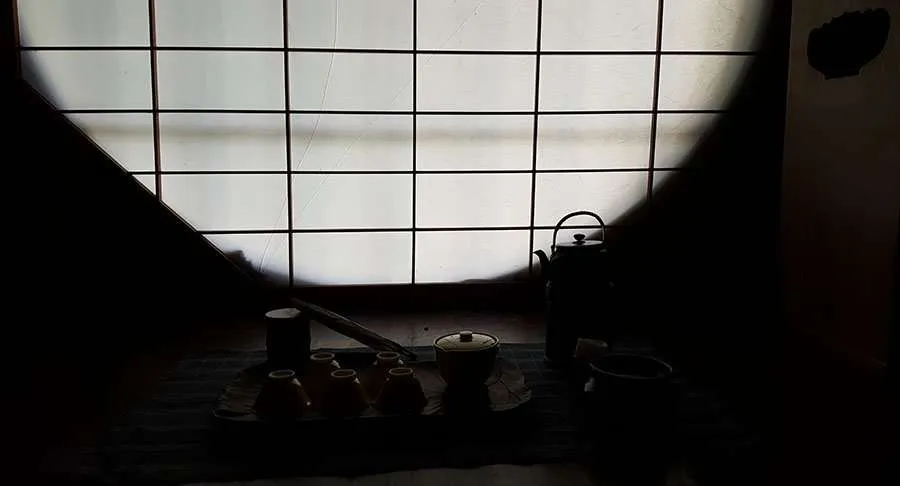

Windows are critical devices for a chashitsu, because they connect the otherwise small, confining room with the outside environment. But the connections are often subtle, because the whole point of having windows is not to access abundant light, but to emphasize the relationship between the host and guest(s) who are sitting inside the small room. The windows could be situated higher or lower on the walls, bigger or smaller, open to outside or semi-closed with shoji.

雲 (kumo): the second floor

As mentioned earlier, one of the rich local merchants bought the Izumo House sometime during the 19th century and added the second floor to make it a guest house. The second floor therefore focuses on securing beautiful views of the downtown and the Seto Inland Sea.

Photo-Tetsuya Ito/by courtesy of DISCOVERLINK Setouchi

The zashiki on the second floor has the “tsuke shoin” in addition to the tokonoma. Tsuke shoin is the receded area next to the tokonoma that has a shelf and small shoji windows. The tokonoma and the tsuke shoin are part of the authentic shoin-zukuri zashiki layout.

煎茶室 (senchashitsu, the sencha tea room)

The 茶道 (sado) uses very finely powdered, high quality matcha to make tea. The sado chashitsu therefore requires the “ro”, a small hearth, so that the host can make tea in front of the guest(s). And there is also the 煎茶道 (sen-cha do) school, that emerged sometime around the 18th century as an alternative to the protocol-ridden sado and enjoy tea gatherings more causally. Sen-cha pours hot water on dried leaves in the same way as we make tea today. There is no “ro” in a sen cha shitsu.

NOTE: These descriptions are about tea rooms in general and not necessarily specific to the tea room at the Izumo House.

The subtle natural light that comes through the shoji window illuminates the profiles of the objects inside.