Wabi-sabi 101: what does “Japanese aesthetics of imperfection” really mean?

Wabi-sabi is a traditional Japanese aesthetic concept that is often considered one of the oldest manifestations of minimalism in art. But what is it exactly? Even the Japanese are not so sure, because it was never really defined as an art or design term. So let’s decode it by looking at its history and application to literature, art and design over time. Here are some hints before we get started.

- Wabi-sabi emerged sometime around the 14~15th century, during which time Japan was going through drastic economic/social changes. First came an unprecedented economic growth, which was followed by devastating civil wars caused by regional military leaders who sought to seize the wealth.

- Wabi-sabi was strongly influenced by Zen, a then-new school of Buddhism in Japan, which was being embraced by military elites and soldiers.

- 茶道 (Sado, tea ceremony) is the most prominent wabi-sabi art, which is a unique art of behavior, attitude or way of life.

Literal meanings of wabi and sabi: it’s Japanese version of “distressed” or “shabby chic”

Wabi and sabi are two different ancient verbs that have common qualities. Wabi (wabu) means to feel disappointed, distressed or abandoned. You may “wabu” if you are forced to live all alone, away from home and family. Sabi (sabu) meant to degrade, decay or rust. A solitary rock in a shady area covered by old moss may look “sabu.” If you are into design or aesthetics, you may already have made connections to the Western aesthetic quality of “distressed” or “shabby chic.” Yes, just like shabby chic, wabi-sabi found beauty in the expressions brew by wear and tear or depreciation. But there is more to it. More than the physical appearance of age, wabi-sabi also embraced philosophical imperfection and the sense of loss as a source of beauty. And this has to do with the social background that allowed wabi-sabi culture to emerge.

Historical backdrops of wabi-sabi

It is commonly believed that the culture of wabi-sabi was born out of the 東山文化 (Higashiyama culture) during the 室町 (Muromach) era (1336-1573). The biggest patron of the Higashiyama culture was the then-shogun 足利義政 (Ashikaga Yoshimasa, 1436-1490), who, much like Ludwig II of Bavaria, squandered his power and public money to create an isolated aesthetic utopia. But unlike Ludwig II, Yoshimasa’s art wonderland focused on simple, no-frills, subdued and subtle beauty.

Yoshimasa recognized the talent of a completely unknown painter, Masanobu Kanou and commissioned some works at his “Silver Pavilion (see below).” Kanou later became the father of the “Kanou school,” which led Japanese painting for the next 400 years.

Yoshimasa’s secluded art wonderland Jisho-ji, commonly known as the “Ginkakuji (Silver Pavilion)”. Ginkakuji is considered as the culmination of wabi-sabi culture, and Yoshimasa’s office Dojinsai (not public) became the template for an authentic Japanese room.

But why did he do this? Yoshimasa’s grandfather, Yoshimitsu, was a very powerful shogun. He aggressively promoted international trade with China and drastically boosted Japanese economy. The Muromachi regime flourished under Yoshimitsu, and Yoshimasa inherited enormous power and wealth as a new shogun. But unfortunately, he lacked the leadership skills to handle it and was overwhelmed. With money came an unprecedented power struggle, but he was unable to keep his administration united. Yoshimasa chose to escape into aesthetic oblivion rather than face the reality. Regional military leaders saw the political vacuum and started fighting each other, causing the Onin-war (1467-1478), the largest civil war up to that time. It lasted for a decade, turning Kyoto from a “flourishing capital” into a wasteland. As the Higashiyama culture blossomed side-by-side with this devastation, it inevitably embraced the sense of loss and the realization that power and prosperity can go downhill in a blink of an eye. People learned the hard lesson that the more money there was, the more devastating its loss became.

Yoshimasa created his Ginkakuji (Silver Pavilion, right) amid pressure and devastation. It is a stark contrast to the lavish “Golden Pavilion” (left) his grandfather Yoshimitsu built. It’s important to understand that wabi-sabi emerged from the harsh conflicts caused by money and power.

Zen and wabi-sabi

The realization that everything created eventually goes away, and that nothing is permanent and absolute, is indeed the core tenet of Buddhism called 無常 (mujo). What’s extraordinary about Buddhism is that it considered mujo as the source of boundless potential, not despair. Everything in this universe comes and goes. People, power, money, beauty are born, grow and eventually die. But death or decline is also about the next birth/growth, and every one of us who is part of this birth-decay loop plays a small but integral part in the infinite whole/universe that continues to grow into something boundlessly large. Nothingness is infinite potential, although it could feel painful. Even before the Muromachi era, traditional Japanese culture embraced mujo and found beauty (mono no aware) in elusive moments: people saw undefinable potential as seasons, natural phenomena or relationships kept changing, or growth became maturity, and then turned into a decline.

Then, Zen pushed mujo-influenced aesthetics to the next level. Zen is a unique school of Buddhism that focuses on meditation, not intellectual endeavors (Buddhism had tens of thousands of textbooks due to its highly philosophical nature), to pursue a religious goal, or Nirvana, which is to completely “empty” your body and soul, dissolve into the vast universe of “nothingness” where you are finally free from any sorrow or pain. Zen expanded its influence as emerging military leaders overpowered reigning aristocrats after the 12th century, and they chose physical and stoic Zen as their school of Buddhism. The fact that Zen relied on stoic conduct/behavior, not intellectual efforts to pursue truth, had a significant impact in elevating Middle Age philosophy and art to a high level of abstraction, in which elements were reduced to ultimate essentials only. Words and meanings were stripped off and objects were disassembled into pure elements. Wabi-sabi was born to reveal the truth of this world, after all kinds of good and bad came and go.

Sansuizu by Sesshu (1420-1506).

Sesshu is one of the most prominent Zen priest-turned ink painting artist.

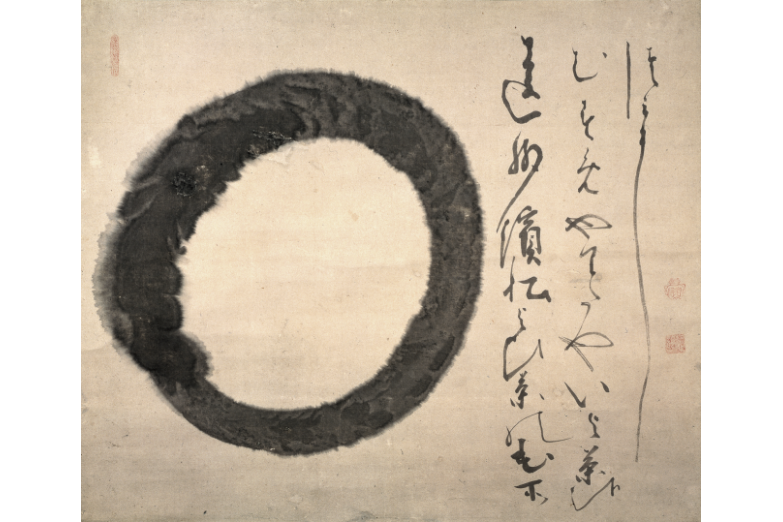

Left: enso by Zen priest Hakuin Ekaku. Zen’s ultimate abstraction can be found in enso, an imperfect circle that could mean so many things about the truth in this world.

Right: Zen garden design is another prime Zen art that was cemented during the Muromach era.

Ashikaga shogun also promoted talented artists that belonged to discriminated social class. Many of them used “ami” names as they became recognized artists, which were used by Jishu Buddhists (Jishu is another school of Buddhism that emerged during the Middle Ages). Noh theater, world’s oldest surviving performing arts, was founded by Kan-ami and Zeami, prominent father-son dancer/screenwriter/producer. Noh is wabi-sabi in that it discovered beauty in presumably negative qualities such as getting old or dying and becoming ghost. Zeami’s pieces are still played today, after more than 700 years.