Aesthetics of “emptiness”: Kenya Hara’s design philosophy

Japanese graphic designer Kenya Hara recently developed the brand identity including logo design for Xiaomi Corporation, a Chinese manufacturer of consumer electronics. In this video, he talks about how he approached the project, which reflects his design philosophy.

What is the secret of his simple, minimalist yet graceful design? Hara often calls it “emptiness,” and it’s something deeply embedded in traditional Japanese design.

Kenya Hara is a Japanese graphic designer who has been playing a pivotal role shaping MUJI’s brand philosophy. As a member of MUJI’s Advisory Board since 2001, along with Naoto Fukasawa, he strengthened the concept of “emptiness,” which is behind MUJI’s minimalist design. What he calls “emptiness” is what we call “Zero” in this project, and it’s expressed by the Chinese character “空.” “空” means sky, void or emptiness. It is the core notion of Buddhism, including Zen. That is the reason why MUJI is often dubbed “Zen.”

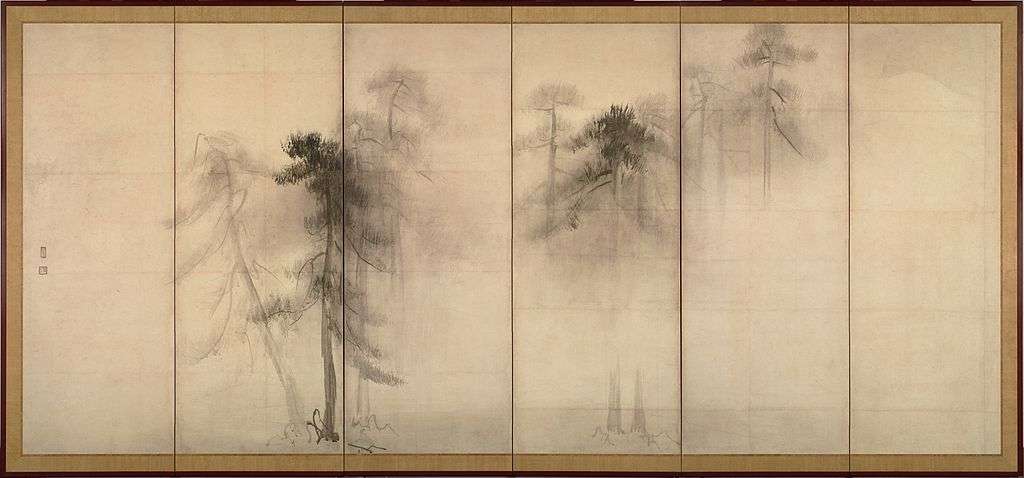

Thinking about zen design will help you to visualize the aesthetics of “emptiness.” As the images of “Zen” suggest, “emptiness” is a realization that the ultimate truth and beauty is not in “existence,” but in “non-existence.” Or not in “absoluteness,” but in “relativity.” Or not in “me,” but in nature. (And “me” is an organic part of nature – an important detail.) It’s striking to remember that the ancient Chinese chose the word “sky” to describe ultimate emptiness. It’s true that there is nothing in the sky, but it’s one of the most beautiful things we can embrace. And if you look closely, you will realize it’s not empty but is filled with boundless potential.

No matter how compelling the the theory of “空” is, it was almost forgotten for a long time, especially during the modern “economy-first” world. Modernization and globalization did not go hand in hand with emptiness. Instead of appreciating the beauty emerging from “less,” modern world was busy consuming increasingly bountiful materials and richness brought about by “more.” And over the course, economic efficiency vanquished aesthetics.

In his highly acclaimed book, “Designing Design,” he starts the first chapter by stating that “We have to listen to the cry.” The cry is coming from aesthetics, he argues, which is forgone in exchange for a drastic advancement of technology and economy. Aesthetics that are delicate, sensitive and subtle, are on the verge of extinction, although it took humans thousands of years to accumulate them.

He further claims that “the progress does not necessarily, and exclusively mean pushing things forward. We are all in between the past and the future. True creativity should not be just forward-looking. We should be able see where the society is heading, by looking it through the past. We have to remember that we have vast knowledge base behind us, and it shouldn’t be underestimated for the sake of future. True creativity should be something that can embrace the past and the future.” (Translation by Mihoyo Fuji.)

“Designing Design” was written in 2003, but after more than a decade, his arguments are getting even more important, now that we have 7 billion people and counting on Earth, and we are starting to feel the pinch. If the Earth had infinite resources, it would have been okay to let technological/economic growth steer our future. Our satisfaction and happiness would have been defined by “more.” And we could have shrugged off the beauty from “emptiness” as a mere nostalgia. But unfortunately it is not the case. We are rapidly depleting our resources. We may eventually reach our limit if we try to progress by solely looking at future and pursuing “more.”

Resource problems are nothing new. Humans have always been faced by resource limitation. Our ability to find beauty in “less” and “emptiness” is our resilience to find happiness in any circumstances, even when they are not favorable. Spending long long time, we have developed amazing abilities to decouple the amount of materials from the amount of happiness, and design things (tangible and intangible) that can let boundless beauty emerge from minimum input. It is time to regain our abilities and resilience.

With MUJI, he has been helping design products that he calls “empty vessels.” MUJI puts significant aesthetic effort to eliminate anything unnecessary, so that their products can become “empty.” This ultimate emptiness inspires and excites users. Once they see the products, they feel inspired because they immediately know that the empty space is for them to add their own ideas. They become motivated to be creative to change the way they live leveraging MUJI’s products. MUJI does not fill the emptiness with “stuff.” They instead leave the absence for the users’ creativity to unleash.

Maybe what Hara is pursuing is something that could be called “sustainable satisfaction,” or “mindful satisfaction.” Ultimately, relying on satisfaction brought about by “more” means relying on external services. Once the service becomes unavailable, your dissatisfaction will come back. But satisfaction brought about by “emptiness” does not rely on external services. You design and own your satisfaction. Because your own it, you don’t have to worry about losing it, or panic trying to replenish it every time you ran out of external service. It’s sustainable and mindful.

Refefence Hara Kenya. デザインのデザイン(Designing Design). 2003. Tokyo, Japan. Iwanami Publishing.

Quotes translated by Mihoyo Fuji.

If satisfaction doesn’t have to be tied directly with “more,” we won’t need many resources to keep our economy up and running, because there would be value other than “more” that would generate money. How would that happen? To explore the potential, start from knowing the potential of Zero. Zero Narratives include specific stories about how and why Zero is humans’ long-standing lab to test satisfaction. If you are interested in Hara’s work, visit House Vision and MUJI stories.