Inspiring sho-sugi ban design and ideas by Japanese architect Terunobu Fujimori

Shou sugi ban, or 焼き杉 (yaki-sugi, or burnt cedar), is a traditional Japanese method to burn the surface of cedar timber to give it a unique rustic look. It also enhances timber’s functionality by oxidizing the surface. Shou sugi ban is a lot more resistant to fire, water, weathering and insects compared to untreated wood. It is believed that Shou sugi ban lasts as long as seventy or eighty years. Since it does not require chemical coatings and leverages the beauty of natural cycle, it is drawing increasing attention as natural and sustainable solution.

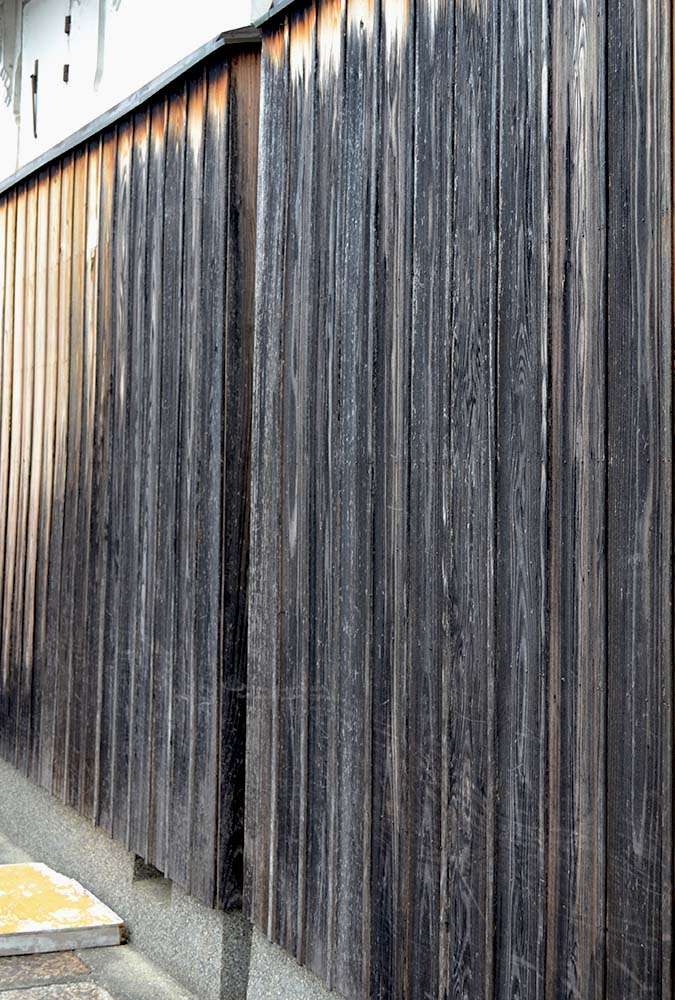

Traditional application of shou sugi ban (yaki-sugi) in Kyoto, Japan.

You can clearly see the effect of weathering.

Until people re-discovered its unique value recently, yaki-sugi was considered old-fashioned and its application had been declining despite its long history. It’s origin is unknown, but one theory suggests that people in Kansai area (including Kyoto and Osaka) started using yaki-sugi to strengthen the bottom of the ships hundreds or a thousand years ago. Kansai area surrounds the Seto Naikai (the inland sea), which has always been the major maritime transportation channel for Japanese.

Terunobu Fujimori, the Japanese architect and architectural historian, is probably the one who unearthed shou sugi ban and elevated its aesthetic values. Fujimori tweaked traditional application by increasing the thickness of slabs from conventional (about 1/2 inches) to an inch. It changes the impression quite significantly: with 1/2 inch of thickness, it is more like cooking a beef steak. It’s a wood plank with a nice brown touch on it. But when it’s an inch thick, the surface will completely turn to charcoal, and the underlying non-burnt portion becomes invisible. It’s just the preference, but Fujimori’s version of shou sugi ban is really “charcoal” from from tip to toe and exhibits a unique primitive strength.

While Fujimori’s Shou sugi ban looks powerfully black, it’s also possible to scrape the black surface off. It’s been the traditional method because you don’t want your hands black after you touch it. When the surface is scraped off, it looks more brown-y and the grains become visible. Japanese cedar is famous for its uniformly linear grains.

You could also add some finishing coat if you wish, depending on your needs. Kyoei Lumber, a Japanese shou sugi ban provider, has some pictures of a variety of finishing touches. The other thing you could worry or be excited about is how shou sugi ban changes the look and feel after installation. You can see the pictures here that show how they change over time.

As the name suggests, Shou sugi ban is basically for “sugi” (Japanese cedar). Sugi is a fast-growing conifer, therefore it is soft, less dense and holds a substantial amount of air and moisture. It burns very fast with the least amount of flame. The traditional method is to make a tunnel using multiple planks, stood upright, and let the flames go through it.

Burners are more commonly used these days, but the burning method should depend on the type of wood – its structure, density or porosity, air/moisture content etc.

As a prominent architectural historian, Fujimori is very cognitive of the origin of architecture — the fundamental question as to why humans needed to build architecture and how. He has deep appreciation on pre-historic peoples’ primitive and rudimentary motivation for building anything structural, and suggests and mud and “charcoal” (or shou Sugi Ban) are two materials still available that inherit the beauty and power of primitive architecture. Although architecture is an endeavor to let something artificial emerge from natural materials, mud and charcoal can stay belonging to nature even after they become part of buildings. They create unique impression by blurring the objective of architecture.