MUJI House: 15 years, 4 models to help owners design their own unique life style

MUJI entered the home building business in 2004 (only in Japan) with the model 木の家 (Ki no Ie, Wood House) to provide a simple, universal, compact yet highly editable platform that is meant to last for decades. It added its forth product 陽の家 (Yō no Ie, Sun House) in 2019, marking its 15th year anniversary in the house construction business. What is unique about MUJI HOUSE? There are a few important qualities.

From left: The Ki no Ie (Wood House, 2004), the Mado no Ie (Window House, 2007), the Tate no Ie (Vertical House, 2013) and the Yo no Ie (Sun House, 2019)

(Images courtesy of Ryohin Keikaku)

MUJI HOUSE design philosophy

MUJI’s houses are very different from the homes offered by conventional home builders, because they aspire to disrupt the way commercial homes are typically designed and marketed today. Instead of touting:

- The size

- The number of rooms

- Modern conveniences

- The number of luxury features

MUJI houses are:

- Designed as strategically small

- Contain only one room (with no interior walls)

- Focus on fundamental functionalities (structure strength/durability and insulation capacity)

- Designed as an “empty” box

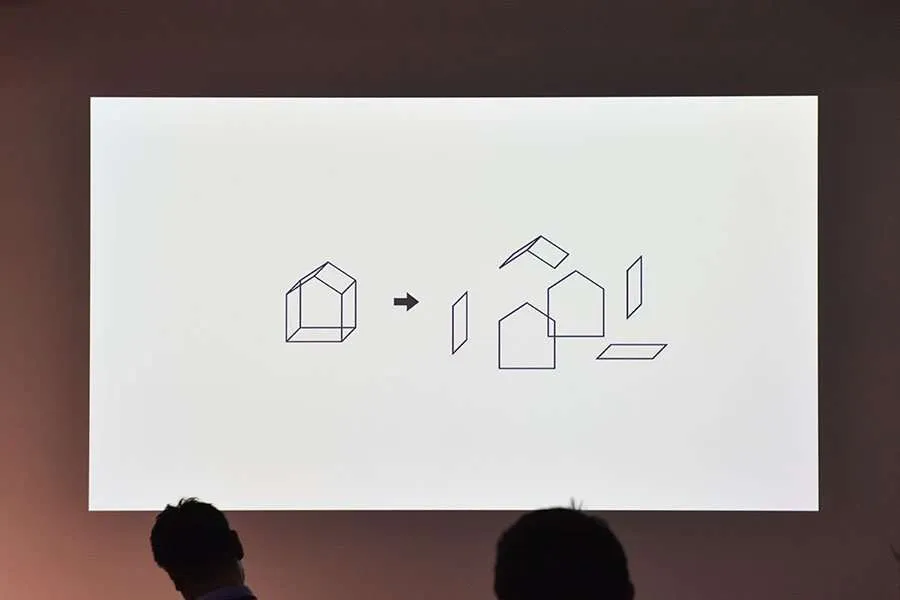

Conceptual drawings of MUJI HOUSE from the press conference for the Yō no Ie in September, 2019. MUJI house provides a sturdy “skeleton” inside which you can freely design the way you want to use it.

The MUJI house design concept, which hasn’t changed a bit since 2004, is “長く使える、変えられる – to provide a high level of flexibility for long-term use.” It provided the quality that had been missing in the conventional housing market in Japan, where the average life of commercial products had been only about 20-30 years, and where houses were irreversibly divided into small rooms, making it difficult for owners to accommodate changing family priorities. Determined to provide a house that could stay reliable and relevant for decades, if not a century, MUJI designed a sturdy and durable framework. But how could you keep it flexible and editable, when there is no way to predict who would live in a particular house, at what point of time in their life, and with what priorities? After a lot of considerations, MUJI came up with a “一室空間 (one-room house)” solution. With a sturdy framework that is achieved using a minimum number of pillars, MUJI house completely eliminated the need for load-bearing interior walls. The result was uninterrupted floors, in which furniture could be used as flexible room dividers. You are free to change the layout anytime you want.

The concept of the “one-room house” comes from the “Series of Box-Houses” designed by architect Kazuhiko Namba, who conceived them in 1995 as a rudimentary, yet highly functional small box that could easily fit into any urban setting. He imagined that the concise, no-frills Box House could be cloned and adapted in different places for different owners, accommodating a unique geographical and social environment. Namba also imagined that the functionalities embedded in a house could evolve and learn to adapt to the surroundings, as if the house was a living organism.

MUJI house offers sturdy frames (skeletons), so that the interior can remain undivided. Good-bye inflexible walls!

By the way, Kenya Hara, one of the most prominent graphic designers in Japan, has been MUJI’s Art Director and helped MUJI cement its “emptiness” (the Zen version of “simple”) design philosophy/aesthetics. He has also been behind MUJI HOUSE’s unique identify, which defies the shortcomings of conventional Japanese housing industry. In his book “Designing Design” (Iwanami Publishing, 2003) he wrote that Japanese commercial houses have been designed aesthetically poorly, unlike clothes or cars for which Japanese brands have earned unique reputation. He believes that it has to do with the way Japanese society Westernized/modernized, even though the Japanese had no clue how to accommodate Western details within a traditional Japanese architectural format. The awkwardness never went away – for example, they introduced Western style rooms but furnished them with tatami mattress without much consideration for details – but business must go on. The industry decided to leverage Western-style appraisal system to advertise house values – such as the number of bedrooms and bathrooms – without really addressing how to raise the aesthetic quality of their offerings (traditional or Western-style, or the combination of both, and in what way?) As a result, the market ended up being filled with unexciting products, and people had few options but to shop for the maximum number of rooms they could afford, whether or not the houses looked pleasing and comfortable.

Hara had a vision to flip this unfortunate situation, and that is what MUJI house does. Instead of considering a house as a piece of property, which is already irreversibly fixed, Hara advocates learning how to create a quality living space based on customers’ changing needs. It does not matter if the house is new, used or renovated. As long as people understand the concept and know how to make tweaks to the house, all you need is a sturdy structure, or “skeleton,” which will allow owners to freely modify and renovate the interior – or “infill.” It’s completely up to owners to decide how to arrange their living space. This is the kind of freedom people never really enjoyed with conventional commercial homes.

Hara’s concept of skeleton and infill is the core of MUJI HOUSE. MUJI also added “air,” which means proper ventilation that was the key for an energy efficient and comfortable living environment.

MUJI HOUSE Basic Features

SE Structure

As mentioned, a sturdy structure is the foundation of MUJI house. But what is the structure of a house? In Western-style, it includes walls. In Japan, the load has traditionally been born by exposed pillars and beams. Houses typically used portable sliding panels (fusuma) or screen doors (shoji) attached within the pillars instead of heavy, unmovable walls, so the rooms opened onto the outside environment, especially when panels were taken away.

A traditional Japanese house used exposed pillars and beams as a load bearing structure, which could open up substantial space.

While openness is priceless when the weather is nice, the combination of pillars/beams and fusuma/shoji offers almost no insulation. It didn’t help security either. Also, since traditional Japanese houses were built using wood, they were structurally vulnerable and prone to fire. As these disadvantages didn’t fit the needs of modern people, this style was rapidly overtaken by a modern and Western framework with sturdy walls which was divisive but good at ensuring security and privacy.

But as technology advanced, Western buildings found solutions to overcome their closed-ness: the rigid-frame structure became popular to allow large openings while ensuring a strong framework, and steel a building elements to be interconnected with rigid connections.

Now, could technology be used to revive traditional Japanese building? That’s what the SE (safety and engineering) structure does. Originally developed to enable the construction of large-scale wooden buildings such as stadiums, the SE structure uses a combination of engineered/enhanced wooden slabs and uniquely designed joints/fasteners in order to realize rigid-frame structure using wood. The result is a soft, natural and warm ambience coming from exposed pillars and beams.

The SE structure also lets you remove the majority of upper floors without sacrificing the sturdiness, so you can enjoy vertical openness which can easily be missing in a small house. It is a default design in most MUJI houses.

The SE structure used in the Ki no Ie (Wood House). You can see exposed load-bearing wooden pillars and beams, which are firmly interconnected to to each each other using special joints/fasteners that minimize the damage to the wood. They are not noticeable at all.

Insulation

With no interior walls and most upper floors removed, the entire house is connected in terms of air circulation. That’s why MUJI puts so much emphasis on insulation: they believe that it is imperative to un-compartmentalize and un-stratify the air throughout the house so that the residents can stay comfortable no matter where they are, with the minimum amount of energy.

There are three focal points for enhanced insulation in MUJI house.

- Walls (both the interior and exterior)

- Glass and frames of the windows

- The floors underneath the glass doors

Walls

Insulation panels made of low thermal-conductive phenolic foam (which has thermal conductivity value of 0.020W/mK) is sandwiched between the exterior and interior walls. The particles of phenolic foam are very small in size, therefore can minimize the amount of heat traveling through it. But that’s not the only wall insulation installed in the MUJI house. The voids between the load-bearing pillars just behind the interior walls are filled with fiber glass in order to eliminate the paths through which warm/cold air could leak outside.

Windows and floors

Window areas are a critical target of insulation for a MUJI house that has large/tall windows that occupy large surface areas. (In case of the Ki no Ie or Yo no Ie, almost the entire surface area of one dimension is glass windows.) Air can leak through glass itself, frames or floors. MUJI takes care of all three.

- Glass: MUJI uses tripe layered glass, in which voids are filled with low-conductive argon gas.

- Frame: In general, energy can travel through the frame areas faster than glass. MUJI house maximizes the glass area by burying the frames inside the walls.

- Floors: We all know that the floor near windows/doors can easily get cold/hot. MUJI house has layers of small air chambers underneath the floor where cold/warm air can be trapped. It also uses a supporting structure under the floor that uses the combination of aluminum and resin to effectively slow down heat transfer from inside to outside or vice versa.

MUJI house has large openings, but the interior is kept comfortable with a minimum amount of energy thanks to the enhanced insulation system.

AIR

MUJI House is also conscious of the surrounding environment and takes advantage of it so that people can live comfortably using the minimum amount of energy. Based on the concept of the “passive house”, MUJI conducts an evaluation of the environment, including the geographical setting, local microclimate, orientation of the house and how wind pass through the area. The results not only inform the design details such as the places/size of windows or how to plant shade trees in the backyard, but also helps people make the most of the blessings of nature – they have a much better idea as to when to open windows and let breeze in, or use sunscreens to avoid the direct sun.

Ramification is significant because not only you need to spend less energy on HVAC equipment, but also you could learn to live without it when not needed.

One of the key elements to living comfortably is to take advantage of the outside environment. You need to know how it changes by time and by season in order to maximize the benefits

MUJI HOUSE products

The solid foundation is the common denominator for MUJI house, but the four models that are currently offered have different goals to accommodate peoples’ needs more precisely.

“Find your own lifestyle” – intro to Ki no Ie, Mado no Ie and Tate no Ie. You can see how the foundation is the same for all the models but the aspirations are different.

木の家 (Ki no Ie ) is MUJI’s first model and best-selling house. As mentioned, it is based on the “Box House” designed by architect Kazuhiko Namba and pursues the “one-room house” system. A typical Ki no Ie has a kitchen, bath and living space on the first floor, and bedrooms and a bath on the second floor.

When it’s owned by a family with two young children, the needs for partitions are minimal. Children can play anywhere in the house, and the family can spend as much time together as they want – to eat, to sleep or to do activities. The high-rise windows strategically face south, so that they can enjoy cool breeze in summer and warm sunlight in winter. The basic Ki no Ie can come in as small as 9.1m x 7.28m (66.3 m2): instead of emphasizing its special lamination, it takes advantage of intimacy.

When owned by a couple of empty-nesters, the design can be tweaked so that they can focus on their own enjoyment. If they want to socialize with neighbors, the entrance area can be extended and enhanced so that it can become a small “community” room, or storage area for gardening. Read more on the Ki no Ie here.

窓の家 (Mado no Ie, Window House) 2007

窓の家 (Mado no Ie, Window House) was inspired by traditional cottages in the old villages in the Cotswolds, in south central England. It is a community in which the neighbors have been sharing the same aesthetic standard, building uniform houses with charming triangular roofs, and taking care of gardens with English roses. In such an environment, the entire community is part of your life, so you want to enjoy it, even when you are inside your house. That’s where picture windows play a pivotal role. Mado no Ie lets you install almost frame-less looking, highly insulating, clear windows wherever you want, large or small. Windows are part of the wall and always the part of the conversation.

縦の家 (Tate no Ie, Vertical House) 2013

縦の家 (Tate no Ie, Vertical house) was imagined as a solution for the super-urban setting in which land is prohibitively expensive. Coming in about barely 3.64m x 8.19m, Tate no Ie offers six “skip” floors that are loosely connected, surrounding the central open areas. You can assign roles to those six components – kitchen, bed, bath or office – and arrange them as you like. Tate no Ie attempts to defy the limitation of space and transforms itself into a comfortable living space. MUJI’s focus on insulation and air circulation plays a critical role to keep the indoor air quality comfortable in this narrow, vertical house that could easily be surrounded by tall buildings in a super-urban location.

陽の家 (Yo no Ie, Sun House) is MUJI’s first single-story house that primarily assumes rural living. It’s a bold step for MUJI to extend its customers from its traditional base that has have been urban/semi-urban residents in their 20’s or 30’s. Kenya Hara, who supervised the Yo no Ie says : “It nailed every detail so that you can live in harmony with the surrounding environment. It can be your last home to live.” Read more about Yo no Ie.