I recently dined at Benihana, in San Francisco, a popular Japanese teppan-yaki restaurant chain. And something raised my eyebrow while my son was ordering the California roll. It’s a sushi plate, as you know. Then the server asked: “Would you like steam rice or fried rice for a side?” I was caught off-guard: “Huh? Did you say ‘rice’ for a side, for a sushi dish?” She was adamant: “Yes. Your options are either steam rice or fried rice, for your California roll. Which would you like?”

[expand title="Read more"]This was shocking to me in three ways: first of all, sushi is a dish of rice on its own. If you have a bowl of fried rice as your side, it’s like you ordered grilled potato for your main, and French fries for a side. It is aesthetically VERY wrong, while aesthetics are an important part of Japanese cuisine. Second, rice is high in carbohydrates. It’s not healthy at all to eat a lot of rice. It’s effectively the same thing as eating a lot of pasta or cookies. Third, rice is a water intensive crop. It takes a lot of work and resources to grow rice. It wasn’t until after WWII that rice had finally become affordable to most people in Japan, to become a national staple. It has never been the aesthetics of Japanese traditional & authentic cuisine to eat A LOT OF rice…well, actually of anything. It’s been about decency, rather than excessiveness.

Because Japan has never been resource-rich, its traditional aesthetics are based on “less is more” philosophy, not “more for less.” But there are a lot of Japanese food and Japanese restaurants (at least as I am witnessing here in California) that tout “more for less.” While the purpose of this post is not at all to criticize such a style, it is dedicated to debunk myths that Japanese cuisine and food are, in general, healthy and natural. Absolutely NOT, if the food is made and marketed forgetting “less is more” fundamentals. Japanese food can be unhealthy to your body and to the environment, if it goes too far – just like any other cuisine.[/expand]

![]()

Before getting into the individual myth, a bit on the general rule. “Less is more” in Japanese traditional food means maximizing the tastiness and flavors nature gave us, without relying on quantity. Seasonality (shun) matters a lot in Japanese food, because it’s the best way to maximize our pleasure, without disrupting the natural balance: find and eat what nature can give us abundantly, in each season.

[expand title="Read more"]Even though modesty is the key, focusing on “shun” is not about a trade-off between quantity and quality: we definitely can feel deep satisfaction without eating a lot, simply by shifting our attention to attributes other than quantity. We can mobilize all of our senses – visual, smell, touch, even the sound of crunch, crunch….to savor our food. It is a joy that can change our views toward food.

Unfortunately, the Japanese cuisine some of us eat in local restaurants may not be authentic, and may depart from “less is more” principle. While it shouldn’t matter whether it’s authentic or not, as far as you like it, the food might not be as healthy or as natural as you’d expect.

A couple of warnings. In general, Japanese food can easily be salty. If you use a lot of soy sauce, and eat a lot of rice to go with your dish, you are consuming something that is high in sodium and carbs. If you add soda and other condiments, you could end up having all of your familiar “guilty” stuff in your one Japanese plate. Plus, the restaurant may be using MSG. If you are seeking healthy and natural in Japanese food, always remember “less is more.”[/expand]

MYTH 1: You can treat rice almost as “all-you-can-eat”

The amount of rice served in Japanese restaurants can be alarming. Rice is not your main dish, but since it’s high in carbs, it’s going to fill your tummy. Focus on and enjoy your actual dishes instead. Especially if you are enjoying alcohol with sashimi or other appetizers, rice can be an overkill. Alcohol is high in carbs (sake is actually made of rice), so it’s an unhealthy redundancy.

I have also seen rice served with shabu shabu. Please. No. Shabu shabu is supposed to be self-complete. Rice and miso soup only comes in as an optional “closer” for the entire meal. Let them wait until the 9th inning, by which time you can decide if you still want it or can skip it. Also, don’t ever think what’s served is the right amount of rice you should eat, because most likely it’s too much.

Fill your rice bowl only about 70 ~ 80 percent: that’s traditional aesthetics of Japanese cuisine. There is also a traditional saying: “Hara Hachibu me (keep your tummy only 80% full)”. It is a wisdom to stay away from overdoing it.

MYTH 2: Soy sauce is dipping sauce

Do you know how much sodium soy sauce contains? It can contain more than three times the amount that ketchup contains. Soy sauce is not dipping sauce: it’s much more condensed. If you eat sushi, several drops per nigiri should be enough. If you feel you need to add more soy sauce to make your food “tasty,” it could be either 1) the ingredients are not tasty enough on their own (maybe not fresh enough), or 2) your taste buds are confused. If you’ve been eating strong flavors for so long, your taste buds could have become numbed, and temporarily unable to detect subtle flavors. Try to start reducing salt, sugar and condiments that deliver strong flavors – it can work as a “detox” process for your taste buds. Once clean and aroused, they will be able to help you enjoy a healthy, decent small dose of seasonings. You will be surprised to see how resilient your taste buds really are.

Soy sauce is concentrated. A few drops should be enough for many occasions. Soy sauce oxidizes and loses its soy bean flavor VERY fast. Keep your soy sauce bottle closed as much as possible.

MYTH 3: More condiments, the better

If you have been to a Japanese teppan-yaki, you might have seen dozens of powders added to the ingredients, on top of a lot of oil and butter. At a sushi restaurant, you often add soy sauce, a ton of wasabi, on top of cream cheese, mayonnaise, chili or Sriracha sauce already applied to the sushi. And by the way, sushi rice is a combination of rice (already high in carbs), sugar, salt, and vinegar. If you think your sushi “tastes” great, it may be because it contains a lot of additives. Step back and think if what you are tasting are actual ingredients, like fish or vegetables, or just a whole bunch of additives.

If strong seasonings and flavors are a stress to your taste buds, to what extent can they stay fine-tuned to notice the subtle savor differences of various tastes, which is what people typically consider as the beauty of Japanese cuisine? If there are too many/much additions, even sushi can be far from being natural, or minimally processed.

In addition to that, many condiments could be artificially processed. Take wasabi, for example. Natural wasabi only grows in mountains where pure, clean water is available. Since it cannot be grown anywhere, most wasabi products on the market include a lot of additives – actually more than half of the ingredients could come from additives. And by the way, the main ingredients could well be horse radish, a popular wasabi substitute. Your wasabi may include zero amount of wasabi! I would guess you don’t want to eat too many additives, especially if you don’t even know what they are, if you are seeking natural and healthy choices.

MYTH 4: Miso soup is an appetizer

Miso soup is a weird animal, in Japanese restaurants. As I wrote earlier, miso soup, often coupled with rice, is traditionally an optional “closer” (only before desert) of the entire dinner, especially 1) when you drink alcohol as you eat, or 2) for formal cuisine such as kaiseki or sushi. But here in the US, it’s served first, sometimes way before your main dish arrives. It’s kind of odd that you have to have this little bowl of often sad, ingredient-less, flavor-less soup, forced to play solo.

In authentic Japanese cuisine, a small bowl of rice is served at the end of the meal. The entire course is primarily comprised of vegetables and protein, and rice adds a decent amount of carbs as a closer. It makes a lot of sense from a nutritional perspective. Miso soup, along with a small plate of pickles (tsukemono), is supposed to accompany rice, which can be plain, as is. Since you are almost full by the time you eat the rice, the miso soup is there to add a subtle aroma and saltiness. It is rather your nose, not stomach, that is enjoying miso soup.

In order to make most of the aroma, timing is everything for miso soup: miso has to be dissolved right before the soup is served, which blends with fish broth, to produce the unique flavor. Unfortunately, I rarely see a bowl of miso soup made with enough attention and care. If you’ve ever seen a flavor-less, aroma-less, and ingredient-less soup, and were wondering why it was even served, you are correct. It is a miso soup deprived of all of its potential value.

It’s much better to make miso soup at home. You could easily create a healthy, natural bowl. Just boil ingredients of your choice such as vegetables or tofu, with fish broth (iriko dashi or katsuo dashi). The only thing you’d have to be careful is not to boil it for too long, or your ingredients could lose their flavors and texture from too much boiling. Tofu is a good example. Once it starts surfacing up, it’s ready – it could only take a couple of minutes. Dissolve the miso after you turn off the heat, because miso quickly loses its aroma.

Fish broth is important, so don’t try to do away with it when you make it at home. There are many products that let you skip the broth-making process. On the right are broth bags that you can simply throw into your pot.

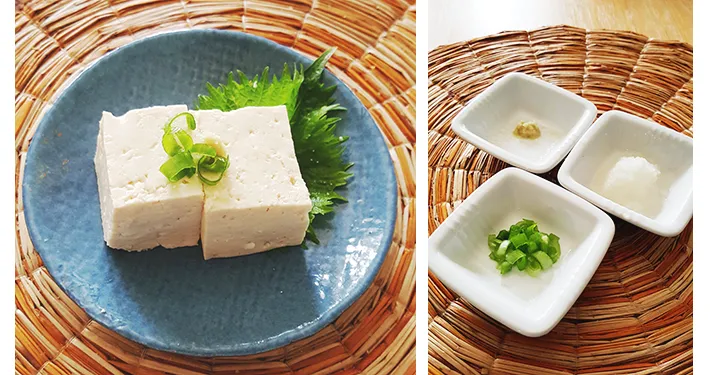

MYTH 5: Tofu is tasteless

The “less is more” philosophy in Japanese cuisine focuses on enjoying naturally occurring flavors. That is the reason why it doesn’t use too many seasonings or condiments, which could kill the delicate natural flavors. Whether its vegetables or fish, every food has its unique taste. Nonetheless, we sometimes find some food “tasteless.” For example, many people think tofu is flavorless. But of course, tofu is made of soy beans. Doesn’t it taste like soy beans and so is not actually flavorless?

Maybe you don’t remember what soy beans tastes like. But as I just wrote, miso has a good aroma, and is made of soy beans. And soy sauce is flavorful, and is also made from soy. So it’s impossible that tofu is flavorless.

Good quality tofu can deliver the aroma and flavor of soy beans. You should be able to tell. But unfortunately, a good quality product is not easy to find. (If you don’t have high quality Asian grocery stores nearby, try Trader Joe’s. Their tofu is pretty good) Like many other Japanese food, tofu is usually eaten with minimal processing. When this happens, the quality of ingredients needs to be high enough to maintain its signature flavor. However, it is often compromised…which could make you believe that tofu is plain, boring, and “flavorless.” And then seasonings and condiments are called upon, to compensate for the so called tastelessness. If you end up eating/tasting additives and condiments, rather than the tofu itself, you are in an unfortunate situation where you are not only missing the opportunity to enjoy tofu, but also ingesting too much sodium etc.

It’s also possible that your taste buds are confused after eating strong flavored food for too long. If you get a chance to buy a good quality tofu, try it raw, with no additives at all, to see if your taste buds can sense any flavors of soy beans.

Hiya-yakko is raw tofu cut into bite sized pieces. Because it’s not processed at all, the quality of tofu is everything. It’s usually served with grated raw ginger, or minced green onions (ao-negi), or shiso (the green leaf with unique scent, a bit like cilantro). Add a little bit of soy sauce and enjoy! The picture on the right is raw ginger, minced green onions and grated white raddish (daikon) – a popular fresh vegetable “yakumi” (condiments) for Japanese dishes.

![]()

“More for less” is now so widely accepted that it may be difficult to find Japanese restaurants that stick to “less is more” philosophy. But you can always try to make something yourself. One of the easiest ones are “nabe (pots),” as long as you can get decent ingredients. There’s no long cooking involved. All you have to do is cut the ingredients and boil them right.

Shabu shabu is a great option, because you can make it at home with a decent budget, and without sacrificing quality ingredients.

Here is what you need. You don’t actually have to have everything, and you can substitute any of them with what you’d like to eat. Also, feel free to try any new ingredients.

Shabu Shabu recipe

- Tofu

- Hakusai (napa cabbage)

- Daikon (raddish)

- Mushrooms (shiitake, enoki, shimeji…)

- Negi (leeks)

- Shirataki or konyaku (starchy noodles you can find at a Japanese grocery store)

- Any type of fish cake

- Sliced meat, beef or pork (Japanese grocery stores sell them as “meat for shabu shabu.” Just make sure to buy good quality ones)

- Noodles (such as udon or ramen, as opposed to shirataki or konyaku – those noodles are high in carbs {typically made of flour} that close the meal)

Steps

- If possible, find a portable (butane) gas stove at an Asian grocery store, so you can make the shabu shabu on your dinner table.

- In a medium-large pot, make a broth (usually with kombu (seeweed), and a bit of cooking sake. If you are too lazy, just boil water…still not the end of the world.

- Start boiling vegetables that take longer to cook (usually daikon and hakusai).

- Add other vegetables, tofu and rest of the ingredients.

- Start adding meat. Because the slices are thin, leave them in the broth for only for 20 to 30 seconds. NEVER overcook.

- Everything is ready. Enjoy!

- In the meantime, try to get rid of residue that comes from the meat, as much as you can. While meat gives great broth, residue adds harshness.

- Add some noodles to close the meal. Add salt and pepper and turn the broth into a noodle soup. Since you now have a very flavorful broth from so many ingredients, you don’t have to add too much to make a great noodle soup.

- Enjoy!